Making Movies: LED there be light!

Posted on Jul 30, 2023

Lighting is an important factor of shooting good video. We illuminate the LED fixtures you should consider

Words by Adam Duckworth

Whether we’re talking still photos or video, quality lighting will transform an image from being little more than a record of a moment into something far more evocative, eye-catching and moody. Masters of the art search out the best natural light, which often means determining the right time of day, and then sculpt it with reflectors to make their subjects appear incredibly three-dimensional, even on a 2D screen or print.

Many of us employ artificial light to lift highlights, act as key or hair lights, create washes of colour with gels, or just add some illumination when levels are low.

A key difference between shooting stills and moving images is that while flash is popular for photography, it doesn’t work for video; filmmaking requires continuous lighting. These aren’t quite as bright as flash and can’t freeze action like a quick burst from a strobe – if they did offer flash-like levels of brightness, we would blind our subjects!

Continuous lights have plenty of advantages, though, for example their what-you-see-is-what-you-get nature. There’s no guessing what the results will look like, as with flash.

For filmmaking, purpose-built LED lighting rules. Of course, you could go the DIY route and use builders’ lights, or even your own household ones. But the vast majority flicker, which looks awful on screen. We can’t see it with our naked eye, but cameras pick it up when the frequencies of the light source and sensor are out of sync. This can be avoided by using 50Hz PAL TV frequency from the UK rather than the US’s 60kHz NTSC, then setting the right frame rate and shutter speed. It can be complicated, but there are charts published of the frame rates and shutter speeds that can be safely used.

Continuous LED lighting avoids such complexity. Conveniently cold to the touch, these have taken over from the hot-running and very large tungsten and HMI lights. Smaller and lighter, LEDs do not need to warm up, nor do they require vast power generators. They’re flicker-free and often controlled wirelessly and remotely via Wi-Fi and Bluetooth.

Talking ’bout an evolution

The original fixtures used small clusters of LED bulbs and were daylight-balanced or bicolour to provide a match with daylight or tungsten light. These were used in everything from small on-camera units to large and soft light panels. Here, brightness is adjusted via a dial, as is colour temperature.

Next came colour LEDs in RGB for red, green and blue – then RGBWW, with two flavours of white: cool and warm. So it’s now possible to obtain any colour your heart desires, which is good for adding creative effects. You can usually dial in gel colours, too. Although adding coloured LEDs means there are fewer white diodes, and so the overall power is reduced compared to a daylight panel of the same size and power rating.

What many wanted was more power, a wider choice of colours and the ability to employ light modifiers – like large softboxes, fresnel lenses and projector attachments. These are the modifiers that have been used on point-source ‘hard’ lights for years in both film and still photography.

This led to COB technology, where instead of separate LED bulbs, these ‘chip on board’ lights had lots of tiny LED chips, bonded closely together to form a single, smaller module.

COB fixtures pump out far more power and, as they are small, perform like a punchy, hard, single-point light source – similar to a studio flash. This makes them easy to use with light modifiers such as softboxes or high-performance reflectors to generate even powerful light. They’re also often roughly the size of studio flash heads, though many are becoming smaller and more portable. At the top end, the largest ones are huge and massively powerful.

The latest also have moved on from RGB to RGBLAC, which adds a twist of lime, amber and cyan in order to produce even more precise colours. Many of the most high-tech models boast built-in special effects, so we can recreate elements such as police lights, lightning flashes, the flicker of a fire, paparazzi flashguns or similar.

Panel show

Many light manufacturers offer small LED panels that can be mounted on top of your camera, or taken off and fixed to a light stand, much like a small flashgun for still photography. However, a miniature light on top of a camera gives a hard and very contrasty look. And though a flash will reach a long way, a small LED isn’t that bright. It’s fine for some fill or if you are shooting in a dark nightclub and can’t see anything. But for creative use, it’s a better to get the panel off the camera hotshoe and use it on a stand, where it creates more of a modelling effect.

While a flashgun is a small point-light source, an LED panel is physically bigger. Larger light sources provide softer, more flattering illumination and are perfect for portrait-style lighting. So it’s a good idea to go for the bigger options here, such as a Rotolight AEOS 2 or Neo 3, which can be used with modifiers to soften the light.

These LED panels put out continuous light in all colours and also offer high speed sync RGBWW flash. So if you regularly shoot stills and video, this could be an ideal buy to avoid having to switch between flash and continuous fixtures. Just don’t expect them to be as powerful as a dedicated studio flash.

Larger light panels offer a more diffuse output, and they also accept softboxes or grids to modify the light. But with size comes more weight and significantly more cost.

Rotolight’s latest innovation is electronically adjustable diffusion, with users able to dial in the exact look they want – while Litepanels provides two versions of its most popular fixtures. Its Gemini Soft is designed for beautiful, controllable light output, while the Hard RGBWW offers punchy, bright light as it uses intensifying lenses in front of the LEDs to focus the output.

For those literally seeking a more flexible option, manufacturers like Godox offer a piece of seriously stiff cloth material that houses LED bulbs. This can either be rolled up for transport, unrolled and bent into different shapes or clipped to rods to maintain its shape.

Just the COB

The latest COB lights include small, palm-sized units such as the Zhiyun Molus range. This collection pumps out 60 or 100W, right up to huge and massively powerful 1200W beasts. The majority of filmmakers use something like a 150 or 300W as a powerful, all-round light. Look out for good-value manufacturers like Aputure, Amaran, Nanlite and Godox.

Many COB lights usefully offer a full spectrum of colours, and are powerful for their size. Without any modifiers, they output a pool of hard-edged light that creates drama. These are made to work well with modifiers, and many come with the Bowens S mount for accessories.

These COBs work brilliantly with umbrellas and large softboxes, as well as focused parabolic softboxes and even projectors and fresnels. Most popular are the parabola-shaped Aputure Light Dome II or Nanlite Parabolic 120. These are ideal for producing soft and flattering light, which is perfect for people as well as product shots.

The deep parabolic shape does cause the light to be more focused than a flatter softbox – and this can lead to a slight hotspot in the middle of the light output. That’s where the small, inner diffuser many softboxes have comes in.

If we deliberately want to focus the light, there are fresnel attachments and projection attachments to use with ‘gobos’ (objects placed in front of a light source), and independent shutters that change the projected image circle into a rectangle, slit or horizontal line.

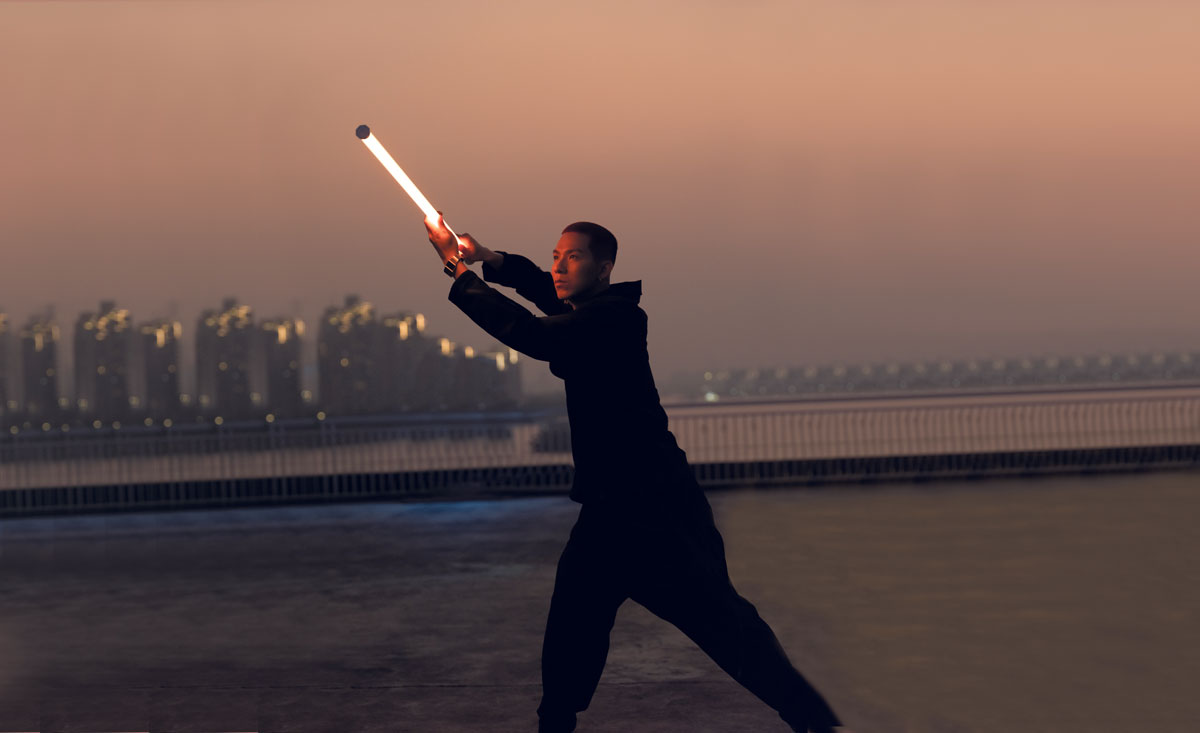

Take the tube

For even more creative effects, LED tube lights are very popular. Many allow us to formulate any colour we like, plus funky patterns in different colours that can be set to pulse like a moving rainbow.

So we can adopt tube lights to create a unique look, or even mount them via clamps to look like regular household or industrial lights. Alternatively, get them up close to your subjects and use them as a conventional light source.

When it comes to lighting, there are even more choices for making movies than in still photography – and at all sorts of price points. So have a go, and see what you can come up with.

Originally published in Issue 109 of Photography News.

Don’t forget to sign up to receive our newsletter below, and get notified about the new issue, exclusive offers and competitions.

Have you heard The Photography News Podcast? Tune in for news, techniques, advice and much more! Click here to listen for free.